The plan to keep warming to less than 1.5˚C is quite straightforward: greenhouse gas emissions need to be cut by 45% by 2030 and then reach net zero by 2050.

The challenge we all face though, is that nearly 200 countries need to co-operate. Decisions on goals, policies, and plans are not made on a “planetary” basis; they are made by nations and their sub-regions like provinces and municipalities.

While the consequences of climate change will be felt across the entire planet, control of the issue is scattered among a myriad of different decision-makers, with varying ideologies and competing interests. That is what makes it a most vexing problem.

What specific responsibility should each country have when it comes to cutting emissions? One would think that the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change would set out what each nation must do for the planet to reach net zero.

But it doesn’t. The Paris Agreement is centered on a sort of vague honor system that asks everyone to set their own targets, called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). It says that countries should set emission targets that “reflect its highest possible ambition, reflecting its common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances.”

Reading that sentence, I imagine the secretary general of the United Nations, António Guterres, rolling out this agreement in a speech to all the countries in the world:

“This climate thing is a big problem which is going to be expensive and difficult to solve. We need all you countries to please go out and do your best because we can only solve this if everyone does as much as they possibly can.

Now, some of you countries are more responsible for this problem than others. And some of you countries may have situations at home that mean you won’t be able to do as much as others. And some of you are also more financially and technically capable to solve this problem. So, we need some of you to step up do more and also help your colleagues.

… But I’m not going to name any names – you know who you are.

Now, talk amongst yourselves and figure this out. We’re counting on you. Good luck.“

(Imagined scenario, not a real quote)

When you consider how much is left to the goodwill of nearly two hundred, independent and often competing parties, it’s really quite remarkable we’ve made as much progress as we have.

There is no enforcement mechanism to the Paris Agreement. As an international treaty, it rests on the willingness of the participants who signed it to abide by it. It is only by naming and shaming countries that there is any sort of leverage to get countries to do their fair share.

Having a common definition of what constitutes “fair share” is fundamental to getting countries to cooperate. It is also controversial because what might be considered fair can be interpreted in many ways.

The current emissions view

In thinking about fairness at the most basic level, it would make sense for the largest emitters to be expected to make the largest cuts. Of the nearly 200 parties who have signed on to the Paris accord, only 12 nations11 account for 70% of current emissions.

The per capita emissions view

Some big emitters like China and India argue that current emissions levels are not a fair way to determine fair share. As emerging economies, they are focused on increasing the standard of living for their citizens to the same level as developed economies. Indeed, on a per-person basis, countries like China and India seem less responsible for emissions than other G20 nations like Australia, Saudi Arabia, and Canada.

The cumulative emissions view

Developing economies like China, Russia, and India also complain that developed economies like the EU and the United States had the opportunity to grow their economies and their standards of living over the last century, and in doing so, it was these countries that contributed the most to the accumulation of historical emissions.

Developing nations complain that it is only fair that these countries do more to cut emissions moving forward because historically, they’ve contributed more to the accumulation of global emissions. Their point is that since carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for somewhere between three hundred to one thousand years, it is the cumulative perspective that is the best indicator of responsibility.

That cumulative argument, while prevalent in the early days of climate negotiations, is becoming less relevant as time passes – if a country is emitting a lot of greenhouse gasses today, it is most likely one of the top historical emitters as well. Ten of the top twelve current emitters are among the top historical emitters as well. Only Saudi Arabia and Iran do not crack the top 12 historical emitters, but they are rising in the cumulative ranks.

The recent actions view

Another argument is that countries that are already making progress in curbing emissions should be viewed more favorably than those that have not. Certainly among the top 12 emitters, there are some very different profiles.

The EU, United States, Brazil, Canada, Japan, and Mexico have all reduced their emission in recent years – although the speed and scale of the reductions vary and none of the reductions are enough to keep warming below 1.5˚C. But at least in these countries, emissions are going in the right direction.

The same cannot be said for the rest of the group. China and India have experienced rapid development of their economies in the past 10-20 years. As a consequence, these nations have seen greenhouse gas emissions skyrocket during the same period.

It should also be noted that for most countries, the latest available data is 2021. Most countries experienced reductions in economic activity during the COVID-19 pandemic, which in turn, resulted in reduced emissions. We will have to wait until all the 2022 and 2023 data is reported to get a better picture of whether emissions are actually down post-pandemic or not.

The committed target view

Perhaps the most important way to judge the fairness of a country’s efforts is to assess how ambitious its emission reduction targets are and how consistent they are with global goals. The near-term goal of the Paris Agreement is to reduce global emissions by 45% vs. the 2010 base year.

On this basis, not one country is doing enough to reach the 2030 goal. Some, like the United States, the EU, Japan, Canada, and Brazil, at least have targets that represent important reductions – from these positions, these countries can make improvements to be on track to contribute to a <1.5˚C world.

For now, China, the world’s largest emitter, is only aiming to halt the growth of its emissions by 2030. But there are reasons for hope with China; it has committed to reaching the net zero target by 2060, has made substantial investments in its energy transition, and has reached its goal for new electric vehicle sales ahead of schedule. Optimists believe that China is laying down the basis for substantial cuts to its emissions after 2030.

The same cannot be said for many other major emitters. Some, like Russia and Iran, are on a trajectory that can only be interpreted as dismissive of global efforts to limit warming. Others, like India and Indonesia, are limited by their dependence on coal in their efforts to meet the energy needs of their massive populations.

The barrier to greater progress is a vested interest in fossil fuels. Only two of the top twelve national emitters are not considered major oil producers (Japan, Indonesia). The emission reduction targets for the rest continue to be impaired by the continued expansion of oil production. Until these countries agree to cap and phase out the production of fossil fuels, global net zero goals will remain out of reach.

The expert view

In the end, there is no single way to assess a country’s efforts in fighting climate change. A complete assessment must weigh a whole number of factors and take into account each country’s unique context and capabilities.

Fortunately, there are independent global think tanks, like Climate Action Tracker (CAT) who do this work.

CAT is an independent research project that tracks government climate action and measures it against the globally agreed Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 1.5˚C. CAT has been providing this independent analysis to policymakers since 2009.

CAT covers all the biggest emitters and a representative sample of smaller emitters accounting for 85% of global emissions and 70% of the global population. For each country, CAT assesses targets, policies, and actions for consistency with the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to less than 1.5˚C.

It rates efforts on an assessment scale ranging from “1.5˚C Paris Agreement Compatible” to “Critically Insufficient”.

The warming estimate associated with each rating indicates what global warming would be if all countries in the world took the same approach as the country being rated.

In evaluating emissions progress, CAT provides 2 kinds of assessments:

A country’s fair share target or pathway can be more or less than the modeled domestic pathway depending on that country’s specific effort-sharing context.

For example, CAT’s analysis figures that it would be fair to ask Canada, one of the world’s most prosperous nations, to commit to a 2030 emissions level that is 14% lower than its modeled pathway target. It would be equally fair if Brazil, as an emerging economy, targeted 2030 emission levels that are 5% higher than its modeled pathway target.

In the fair share concept, some countries would also be expected to provide financing to help other countries reach their goals. Again, CAT assesses a country’s financial commitments to climate change where applicable.

Finally, CAT produces a summary rating of each country’s efforts which weighs the ambition of its targets, the impact of policies and actions, and, where applicable, plans to finance emission reductions in other countries.

Looking at the top 12 largest emitters – not one is rated any better than “Insufficient” and most are rated “Highly Insufficient” or worse.

In fact, there is not a single party to the Paris Agreement whose emissions reduction plans are rated as compatible with 1.5˚C. There are nine top-rated countries that have been assessed as being “Almost Sufficient”.

It’s tempting to praise the efforts of the countries on the “Almost Sufficient” list. However, other than the United Kingdom and Norway – all of these countries have very low rates of economic development and per capita emissions to begin with. Even if these countries don’t cut emissions very much at all, their profiles are still compatible with the 1.5˚C compatible scenario on a fair share basis.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

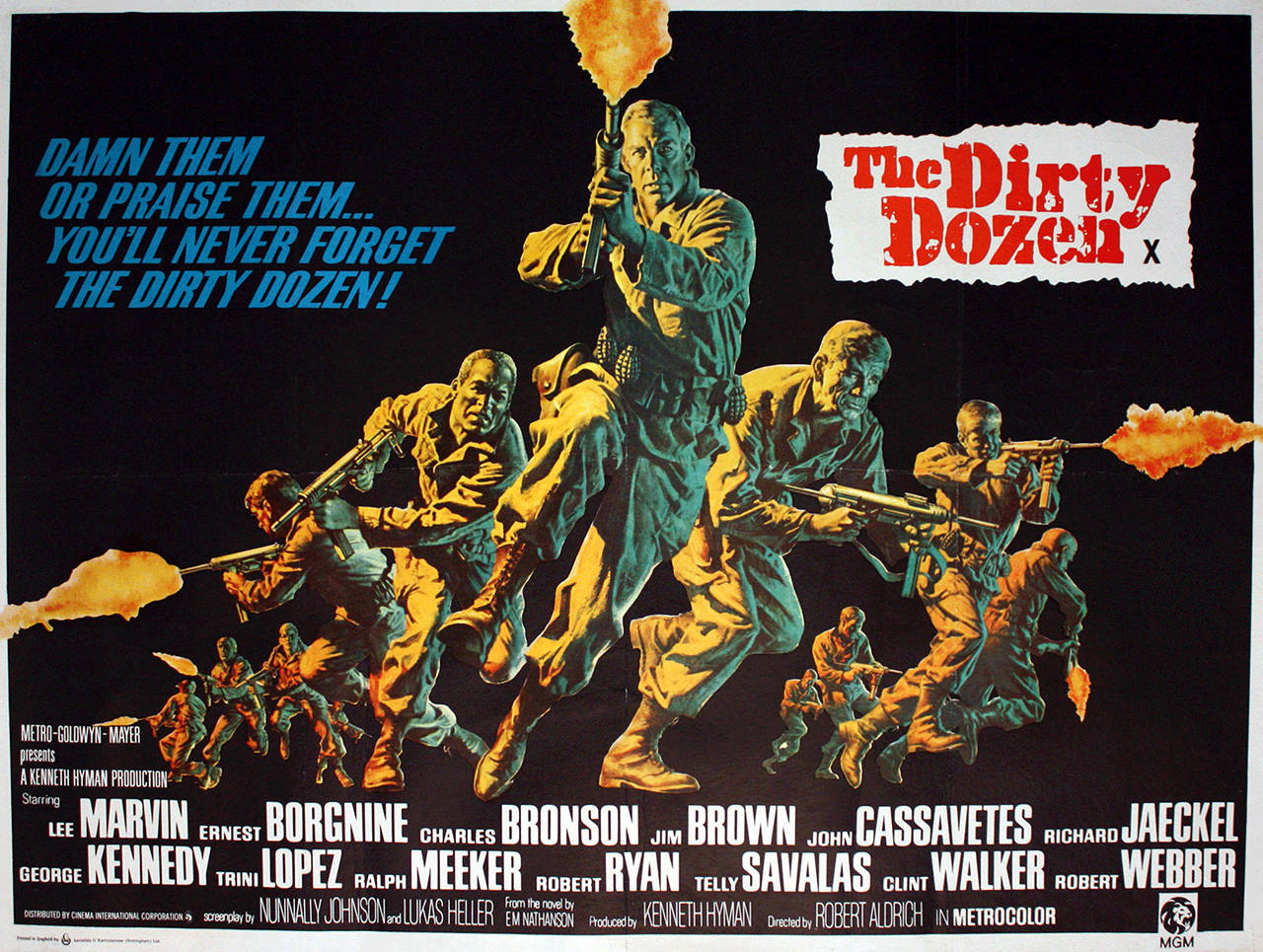

The Dirty Dozen is the title of a 1967 war film about a group of convicted criminals being offered a difficult deal: carry out a military mission so dangerous, that you’ll likely be killed, but if you do survive, you’ll be set free. The only chance you have to come back alive is to work well together.

The concept is similar to the classic “Prisoner’s Dilemma” – a model of game theory that is often used to illustrate the challenge of climate change.

In the thought experiment, two criminals are held in separate cells. Each is offered the same deal: testify against the other and get set free, while the other receives a three-year prison sentence.

If both prisoners cooperate by refusing to testify, each will receive a one-year sentence. If both testify against each other, each receives a two-year sentence. Crucially – the prisoners cannot discuss their choices with each other.

The most rational course is to cooperate. However for players, the benefit of cooperation remains costly, the temptation to “defect” for individual reward is strong, and it is hard to trust that your partner won’t take advantage of you as a sucker.

In the climate crisis, all nations are similarly interdependent. The best outcome can only come from cooperation, but it is difficult and costly. The temptation to maximize national economic benefits at the expense of the climate is very powerful and mistrust among nations is rampant.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is usually solved by iteration – after a few rounds, participants eventually come to realize that they do better by working together.

In the climate crisis, there can only be one round – but unlike the Prisoner’s Dilemma – we do get to talk to each other. ■

- If you’re being strict, the European Union is not “a country” but actually 27 countries. For climate change policy and analysis, however, it is usually treated as one party. The EU is governed by common institutions, has a common climate policy, often negotiates as a bloc, and submits a single combined NDC for all member states. The largest emitter in the EU is Germany. If we treated all European countries separately, the EU would drop off the list and Germany would take the number 12 spot. ↩︎

Leave a Reply to Meredith Cancel reply