The headlines have been ablaze lately, with news of record-breaking temperatures seemingly published every day.

According to a report published by The Guardian, national heat records have been broken in 15 countries so far this year. An additional 130 monthly national temperature records have also been broken, and tens of thousands of local record highs have been registered at monitoring stations from the Arctic to the South Pacific.

The steady stream of records can be overwhelming and it is only natural to want to tune out the news. But it is important to remain focused on what these global temperature trends really mean for us all.

Here are five points to consider about the recent string of record-setting temperatures:

1. The entire planet is consistently setting new temperature records

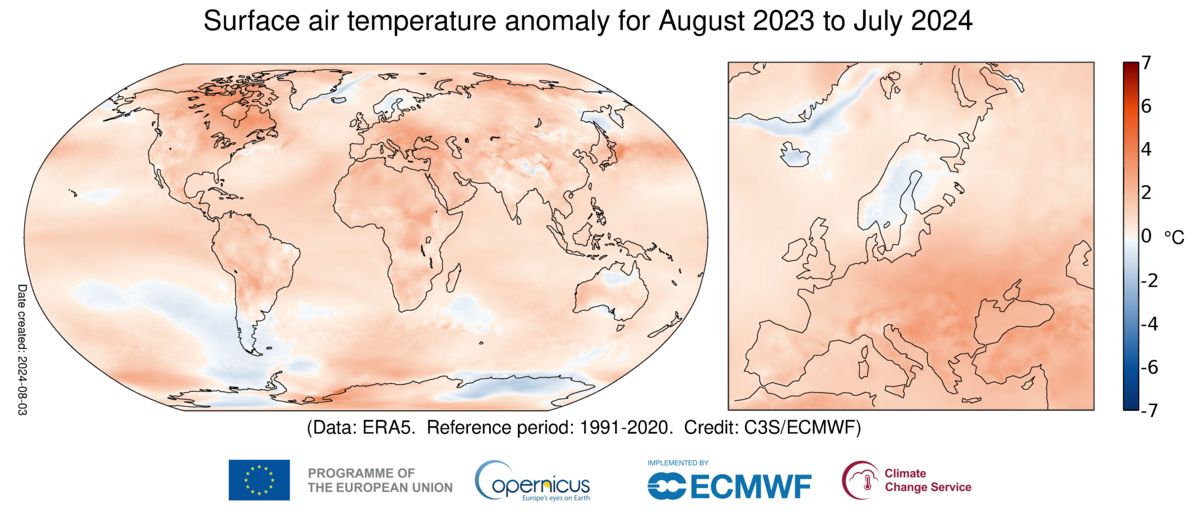

Every month for over a year, the world has been experiencing unprecedented temperature increases. Every month, from June 2023 to June 2024, the average monthly global surface air temperatures set new all-time records.

The data comes from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) – an information service provided by the Copernicus Earth Observation Programme of the European Union.

In their most recent update, CS3 announced that the monthly streak of new records was finally broken – the global average temperature increase for July was only the second-highest monthly average ever recorded – June 2023 remains the all-time record. However, in July 2024, the Earth set two new records for the hottest days ever – July 22 and July 23.

2. Temperatures have increased more than 1.5˚, but the climate hasn’t – yet.

CS3 often expresses temperature results as the change in temperature vs. the “pre-industrial average” – what it was on average between 1850 and 1900. That was the time before the world started using fossil fuels as its primary energy source and before greenhouse gases started increasing the heat-trapping capacity of our atmosphere.

It’s a useful way to express the data because it’s comparable to the global goal of the Paris Agreement, to limit warming to less than 1.5˚ vs. the pre-industrial average.

Overall, the global average temperature for the past 12 months (August 2023 – July 2024) was 1.64°C above the 1850-1900 pre-industrial average.

You may be thinking: “Wait – aren’t we trying to keep warming below 1.5˚C? If it was more than that in the last 12 months, doesn’t that mean we’ve lost?”

Well, yes and no.

Globally, the temperature really has been more than 1.5˚ warmer than pre-industrial times on average. But the temperature in any one year may not be representative of the climate. When scientists refer to the climate – they mean a longer-term period of consistent environmental measures – typically 30 years.

On a 30-year basis then, the climate has warmed by 1.28˚ vs. the pre-industrial period. But given the trends, the scientists at CS3 now estimate that, unless we address emissions, we are likely to reach 1.5˚ by March of 2033.

Even if temperatures do exceed 1.5˚ on a long-term basis – it won’t mean “it’s over”. We will still need to put all our efforts into cutting emissions. It will just mean that the environment we will be working to protect from further damage will be warmer than we’d hoped.

3. Canada and the Arctic are warming 2x to 3x faster than the global average

Global average temperature data makes for good headlines, but averages are an abstraction. No one experiences average temperature – they experience the actual temperatures where they live and global warming is not evenly distributed. Unfortunately for Canada, our temperatures are warming twice as fast as the global average and the North is warming at 3 times the rate.

Arctic amplification is one of the reasons why. Regions closer to the poles are warming at a faster rate than the global average because ice and snow, which reflect sunlight, are melting, reducing the Earth’s albedo (reflectivity) and causing more absorption of heat. In contrast, regions closer to the equator experience more stable temperatures due to the consistent solar energy they receive year-round.

4. Your mileage may vary: Local land-use practices can further amplify warming

Another factor that impacts the heat we experience is the degree of human activity and how land is used.

Urban areas, where concrete and asphalt replace vegetation, can experience more intense warming known as the urban heat island effect. Deforestation and land-use changes also affect regional climates by altering the local carbon cycle and reducing the ability of natural landscapes to absorb CO2. Temperatures can vary from neighbourhood to neighbourhood based on urban planning policies affecting development density, construction practices as well as preservation of tree cover and green spaces.

A 2022 analysis by the CBC produced some startling satellite images that illustrate heat disparities within major Canadian urban centres. The image of Montreal for example, below, shows clearly how more developed areas are warmer (red/orange) compared to undeveloped areas, parks and even developed neighbourhoods with greater tree cover (light / dark blue).

5. Record temperatures underly the range of knock-on effects we are experiencing today.

The rising temperatures are not just about discomfort; they set off a cascade of severe consequences. A study published just published in July concluded that in 2023 nearly 48,000 people died in Europe due to extreme heat.

Higher temperatures lead to droughts, which can devastate food production, strain water supplies, and hamper our ability to generate electricity from hydroelectric facilities.

Drought conditions also fuel wildfires, which not only cause widespread destruction but also exacerbate climate change by releasing massive amounts of CO2 and reducing the cooling effect of forests — creating a vicious feedback loop that drives temperatures even higher.

We are now living with the early stages of these effects. One example: as I write this, the Jasper Wildfire Complex, having already destroyed nearly 40,000 hectares, including about a third of the town of Jasper, remains out of control.

Warming is also making our rainfall and storms more extreme. Warmer oceans are supercharging hurricanes, increasing their intensity and destructiveness. For every degree of warming, the atmosphere can hold 7% more moisture, leading to record-breaking rainfalls.

This summer, record rainfalls and flooding have been affecting municipalities across Canada. Just days ago, my city, Montreal received an unprecedented 157mm of rain, a new all-time record. Highways closed, sewers backed up, and people’s homes were damaged.

A call to act

While global averages help us understand the overall trajectory of climate change, it’s the local impacts—like those were are now feeling in Canada—that truly drive home the urgency of the situation. As we approach critical thresholds like the 1.5°C mark, it’s important to keep in mind that these numbers are not just abstract concepts — they represent real, lived experiences that are becoming more extreme with each passing year.

Understanding the nuances of temperature data is not just for scientists; it’s for everyone. Whether we are debating the significance of a new record or grappling with the changes in our own backyards, the data demands our attention. And with that attention must come action, as the consequences of inaction are growing clearer and more severe with each passing year.

Leave a Reply